Editor’s View: Why frequent flyer programs are the main game for airlines

What we'll be covering

With over 12 million Qantas Frequent Flyer and 10 million Velocity Frequent Flyer members respectively, many people are aware of the value and benefits that frequent flyer programs can provide to their personal travel budgets. But do many people, not to mention aviation experts, consider the financial benefit that they provide airlines?

This Editor’s View takes a look at the importance of frequent flyer programs to airlines, and ultimately, to us customers, who rely on airlines remaining profitable and offering a service that allows us to remain connected with the world.

History of the airline industry

Pre deregulation era

For many of us, it’s hard to imagine a time that when you asked someone if they were a frequent flyer, you were actually being literal and not asking if they are a member of an airline’s frequent flyer program. This was in the era before deregulation started to take hold in the airline industry and frequent flyer meant just that, a person who frequently flys.

In the United States, the birthplace of frequent flyer programs, deregulation occurred in 1978, with the first frequent flyer program that tracked miles flown and issued subsequent rewards created in 1979 by Texas International Airlines.

Here in Australia, deregulation didn’t occur until 1990, with the first frequent flyer program created by Qantas in 1987, with Ansett Frequent Flyer and later Global Rewards following in 1991.

This era before deregulation was, no surprise, heavily exemplified by high levels of regulation that mandated the service levels to be maintained, routes that could be flown and prices that could be charged for each route, to the exact dollar. It nearly always meant prices being no more than $1 apart between airlines, which resulted in the value proposition amongst them to be almost identical, with the only point of difference being that airlines could compete on their product and service offering.

In this era, airlines competed on product & service.

Post deregulation era

Fast forward to 1978 and 1990 in the United States and Australia respectively and you come to an era where deregulation unshackled airlines from their regulatory straightjacket and for the first time, allowed them to compete on both routes and prices.

Prices for the same routes were no longer just $1 apart between airlines, and although the service and product were not exactly identical, they were still very close, at least in Australia anyway, with usually just the branding and colour scheme differing.

Many new entrants looked to take advantage of the deregulated market during this time, with the most notable entrants into the Australian market being Compass Airlines, Virgin Blue, Impulse Airlines and OzJet.

While some of these new entrants were looking to introduce product or service differentiation from the established players, all were looking to compete heavily on price in an attempt to undercut the more established players, such as Qantas, Ansett and Australian Airlines. This was starkly different to pre-deregulation.

Other airline business models also began in during this era, such as the ultra-low-cost models of Laker Airways, Southwest Airlines, Ryanair and EasyJet.

An interesting video filmed in the late seventies shows the struggles that United Airlines faced to adjust their operations following deregulation.

Make sure to set some time aside to watch this, as it goes for just over 50 minutes, but I highly recommend it for those aviation enthusiasts who like to know the commercial aspects of running an airline. The video clearly shows how the industry has matured and become more efficient over the decades (not to mention how society has changed too – no smoking in Boardrooms anymore!)

In this era, airlines mostly competed on product & service and price.

The last fifteen years

The last decade and a half have seen a substantial change in the aviation sector. In the US, we saw a number of mergers from what was a heavily fragmented market. The major merger began with Delta and Northwest, followed by United and Continental, Southwest and AirTran and finally American Airlines and US Airways.

In Australia, we saw the re-emergence of a full-service duopoly that dominated most of the 1990s in Qantas and Ansett Australia, but with the addition of low-cost subsidiaries Jetstar and Tigerair to the new duopoly groupings, Qantas and Virgin Australia respectively.

This current era has also seen the gap in market segments from the pure ultra-low-cost airline to the full-service airline reduce, with both ends of the market tweaking their product offerings towards a more centre-of-the-market proposition.

For example, many ultra-low-cost airlines such as Ryanair began to introducer pay-per-use offerings normally found in traditional airlines, such as the ability to reserve your seat and access priority boarding, while traditional full-service airlines like Air New Zealand began to move away from an all-inclusive offering in their short-haul routes in favour of a pay-per-use.

This shift also extended into the frequent flyer space, especially with the low-cost airline end of the market beginning to introduce frequent flyer programs in contrast to the early days of these airlines, where they shied away from introducing features in excess of only the bare-bones requirements for running an airline.

Great examples include Southwest Rapid Rewards, Air Asia BIG and in the case of one of the United States most ultra of low-cost airlines, Frontier Airlines, they have even introduced status levels in their Frontier Rewards program.

In today’s era, airlines compete on product & service, price and loyalty.

So how do frequent flyer programs make money?

If there is one question that I hear time and time again, it is how frequent flyer programs make money for an airline. If they are giving away free seats, then aren’t they losing money?

Well, on the face of it, that’s exactly how it appears. But dig a little deeper to find out how they actually monetise their frequent flyer programs and it won’t take long for you to conclude that being generous and rewarding is not necessarily their primary motivator, although hopefully a motivator nonetheless.

Airlines sell their frequent flyer points to third parties such as banks, retailers, car rental companies and hotels, at a set price and usually in bulk, with the third parties then offering these points as bonus points to incentivise new and possibly existing customers to do business with them.

In effect, it’s just an alternate customer acquisition strategy to that of traditional strategies such as television and print advertising. I know for myself, that if the choice comes down to an annoying 30-second advertising jingle or an offer of bonus frequent flyer points, which one I would find more incentivising!

The figures don’t lie

Whether frequent flyer programs are a help or hindrance to the financial performance of an airline has been a debatable topic, so to answer this question, at least within the Australian context, I have created a time series of underlying Earnings Before Interest (EBIT) chart for both Qantas and Virgin Australia groups by operational segment.

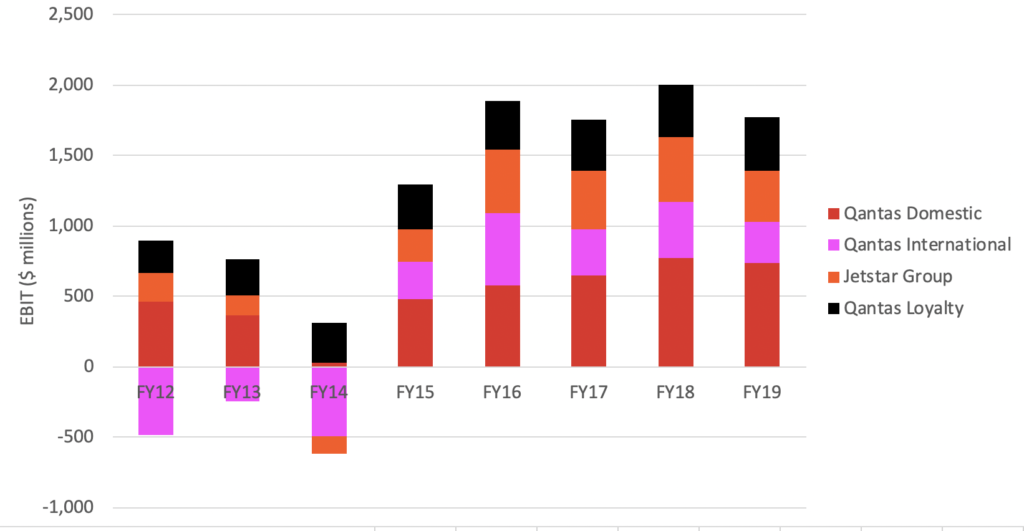

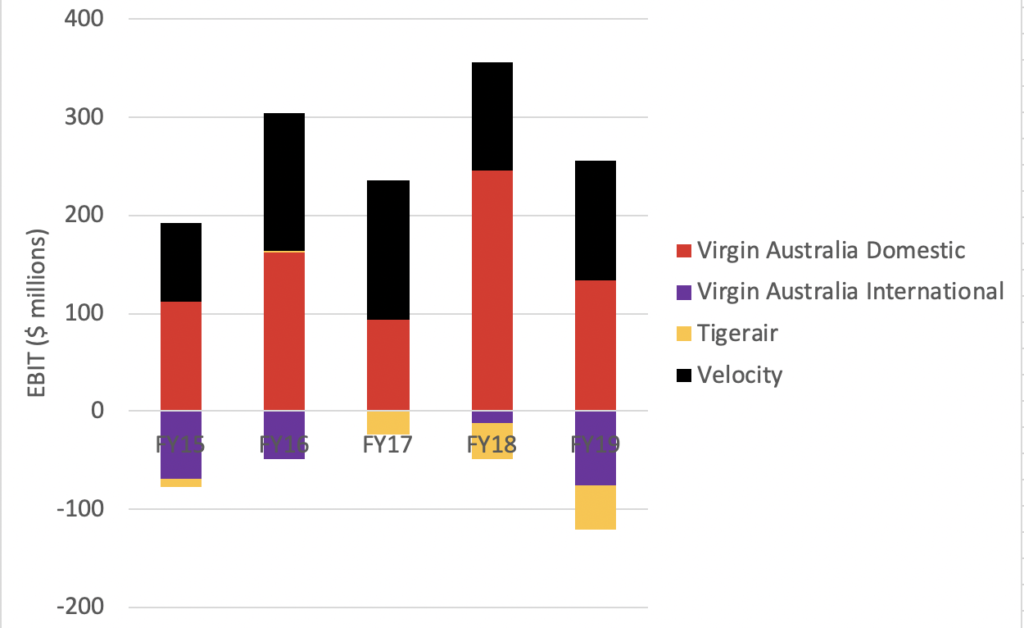

Note that Qantas Group only began to report on the EBIT of Qantas Frequent Flyer from FY12, while Virgin Australia Group started reporting the EBIT of Velocity Frequent Flyer from FY15.

Beginning with the Qantas Group, if there is one thing that stands out from the chart below is how profitable the airline has been since FY15. What is also striking is the consistency in positive earnings for Qantas Loyalty, even through its toughest year in FY14 (albeit other segments were heavily hit with accelerated depreciation expenses in that year).

In many years, the Qantas Loyalty program was the second most profitable division behind Qantas Domestic and even the most profitable division in FY14. Qantas Loyalty is likely again to take the top mantle in FY20, with the impact of COVID-19 all but evaporating the revenue stream of its other segments in the second half of that year.

The consistency of material positive earnings year on year is even more exemplified at Virgin Australia, with the Velocity Frequent Flyer segment consistently achieving positive earnings in the last five financial years, while other segments such as Virgin Australia International and Tigerair struggled to even break even.

The consistency of positive performance in the frequent flyer segments of both airline groups should not come as a huge surprise, given that these segments have very little capital expenditure and are not exposed to anywhere near the same level of volatility in their earnings as the mainline operations.

Just think about what the mainline operations have to deal with. On the expenditure side, this includes large price movements with labour and fuel, not to mention shocks like those that were experienced during the 1973 and 1979 oil crises. And on the revenue side, airlines must contend with the cyclicality of the macro-economy, as well as revenue shocks such as the September 11 terror attacks, the 2008 global financial crisis, and fo course, the COVID-19 global pandemic.

So given all this, is it any wonder that frequent flyer programs are considered by many within the industry and airline analysts alike as being the ‘the jewel in the crown’ for airlines?

The circular benefits of frequent flyer benefits

While it is true that frequent flyer programs are the ‘jewels in the crown’ for airlines, the product that underlies the program will determine how well it actually shines.

Frequent flyer programs generate revenue from selling points to third parties, and in order for this to be a profitable exercise, the program needs to generate enough interest from partners who see the benefits of the airline’s points to its own customers. And from the airlines perspective, the more members it has in its loyalty program, the more it can charge for its points.

Therefore, the benefits that flow from frequent flyer programs are in a way circular. A strong product offering by an airline will entice people to join and become active in the airline’s frequent flyer program, while a strong program with many redemption options along with aspirational redemptions will entice members to fly with the airline. The two are intrinsically linked.

This brings me to the sale of Virgin Australia to Bain Capital. The airline’s entry into Voluntary Administration in April 2020 has led to many different opinions on what the make-up of a Virgin 2.0 should look like, but what I have been amazed by is the lack of discussion around the Velocity Frequent Flyer program.

Many commentators seem to have a singular focus on how the airline’s operations could be improved, with the frequent recommendation to revert the airline back down market to a low-cost Virgin Blue model constantly mentioned, without any consideration on the earnings impact this could have on the consistently profitable Velocity segment. Such a focus made sense in the era of pre-deregulation, but not so much now.

From the public statements issued by Bain Capital, it appears that the value of Velocity is not lost on them. In fact, they appear to have placed the program at the centre of their rebooted Virgin 2.0, looking to improve the user experience for Velocity members and improve the Velocity offering, which they see as having great potential.

I have frequently made mention of the fact that Qantas Frequent Flyer is one of the best and most profitable frequent flyer programs in the world. Plenty of members, partners, earning and redemption opportunities have made this so, and as the EBIT chart showed, has consequently been an important contributor to the profitability of the airline.

Done correctly, frequent flyer programs can be a great profit driver and stabiliser for an airline.

The future of loyalty programs

Given the profit potential of frequent flyer programs, and the greater digitisation and the shift of the economy and business to accruing analytics or ‘big data’ on their customers, their future should remain strong.

From their early inceptions as simply a way to reward flyers for their loyalty and provide a method to fill seats that would otherwise be left empty, frequent flyer programs have morphed into large scale loyalty programs with a myriad of partners and a variety of rewards on offer, including the most recent addition to the Qantas program, Afterpay.

But still today, there are some limitations that prevent these programs from being even larger, but with some exciting technology around the corner, many of these limitations may soon be a thing of the past.

The most common obstacle faced by many would-be partners of programs is the lack of required IT infrastructure or staff to effectively communicate with the loyalty programs and processing eligible point-earning transactions from customers in a reasonable timeframe.

Enter Blockchain technology; mooted to be an ever-increasing component of future frequent flyer program back-end structures. This technology is expected to allow airlines to correspond with their partners on an instantaneous basis, and remove the need for costly integration of IT systems between partner and airline.

A result is an increasing number of smaller business, who at present are effectively locked out of participating as partners in frequent flyer programs, being able to access these platforms. Think your local mechanic, corner store or smaller chemist for example.

Whether this technology, or something else ends up being the catalyst for the frequent flyer market expanding, the good news is that frequent flyer programs look set to continue their growth and provide members with even more earning and redemption opportunities into the future.

Summing up

The frequent flyer market is constantly changing, and it is hard to believe that just three decades ago this market did not even exist, given how popular these programs have become with the general public.

Many people do not understand the financial mechanics of frequent flyer programs and how they can actually be profitable for airlines, and I hope this article has helped to explain them.

The past performance of frequent flyer segments have shown us that they are consistently profitable, and this should not be a surprise given the low amount of capital expenditure required to maintain these programs, and unlike the traditional mainline segments of airlines, the expenditure does not grow in line with the growth in operations.

What frequent flyer programs will look like in the future is yet to be determined. But what is clear for now is that the intrinsic value these programs have, due to their large customer databases allowing them to effectively sell points to thirds parties for their own customer acquisition strategies, makes these programs the main game for airlines.

Check out the other Point Hacks Editor’s View articles here →

Thanks for letting me know and you are right. After further digging, I since found out that Qantas launched their program in 1987, with Ansett launching theirs in 1991. I have updated the article accordingly.

I hope you enjoyed the article.

What are your thoughts on being able to once again transfer our Velocity points to Singapore Airlines Kris Flyer.